To understand the origin of most autoflowering genetics, it’s important to consider the cold regions of Eastern Europe (Hungary, Southern Siberia, Russia, and others) and Central Asia, where the first wild Cannabis Ruderalis strains emerged. In these areas, harsh climates—especially the cold temperatures and long winters—offer only three or four months each year with adequate conditions for cannabis growth and reproduction. It’s likely that these strains developed the unique autoflowering trait as an adaptive advantage, allowing them to flower and produce autoflower seeds within a brief period, thus ensuring the survival of the species in such inhospitable environments.

Cannabis Ruderalis is a subspecies of Cannabis Sativa. Soviet botanist Dmitri Janischewsky first described and catalogued it in 1924. At the time, it was considered a "bad weed," due to its low THC content and lack of appeal for medicinal or recreational use. It was also deemed unsuitable for industrial purposes, like fiber or paper production, because of the small size of the plants.

Today, wild autoflowering plants similar to Ruderalis can still be found in some regions with a history of cannabis cultivation, especially central North America and Canada, though smaller populations can occasionally be found across the country. These plants have adapted to their environment over time, and without human intervention, have lost many of the traits that are typically selected by growers.

It’s possible that autoflowering genes are present in the gene pool of most cannabis strains. Ruderalis strains, along with other wild autoflowering plants, may have developed from naturally selected populations of Cannabis Indica with short flowering times. Current consensus suggests that both "domesticated" and wild cannabis strains share a common genetic origin, making it likely that many cannabis strains still carry autoflowering genes in their DNA.

At Sweet Seeds®, we’ve observed that the autoflowering trait behaves as though it may result from "damaged" genes—genes that no longer respond to photoperiod changes and thus cannot flower based on decreasing light hours.

After the 1970s, a few pioneers at cannabis breeding began to recognize the hidden potential of autoflowering strains and started crossbreeding them with high-THC strains. Their goal was to harness autoflowering traits like fast flowering, short stature, cold resistance, and resilience against local pests and diseases in plants with higher THC levels and more desirable aromas. This marked the beginning of breeding programs aimed at incorporating these autoflowering traits into high-THC strains.

The first documented experiments to cross Ruderalis with high-THC strains were conducted by Ernest Small from Agriculture Canada in Ontario during the 1970s.

In the 1980s, famed breeder Neville, owner of the pioneering Seed Bank, experimented with Ruderalis hybrids, including crosses with Mexican strains, Skunk #1, and various Indicas. Although these hybrids matured earlier than typical Mexican strains, they had lower THC content and were quite inconsistent in flowering time and calyx-to-leaf ratios.

Meanwhile, on British Columbia’s Gulf Islands in Canada, an anonymous outdoor grower noticed that a photoperiod-dependent strain he had cultivated for several years—usually harvested in October—contained a few plants that matured much earlier, around late July or early August. Through years of selection, he developed a seed line that retained the autoflowering trait along with the effects and aromas of his cherished strain. This work led to the creation of Mighty Mite.

Mighty Mite quickly gained popularity, especially among Canadian growers who valued its ability to be harvested before summer’s end and before the arrival of mold. In northern regions, it often replaced fast Indicas that had been adapted to cold climates. Later, it was also cultivated by indoor growers and hybridized with more potent strains.

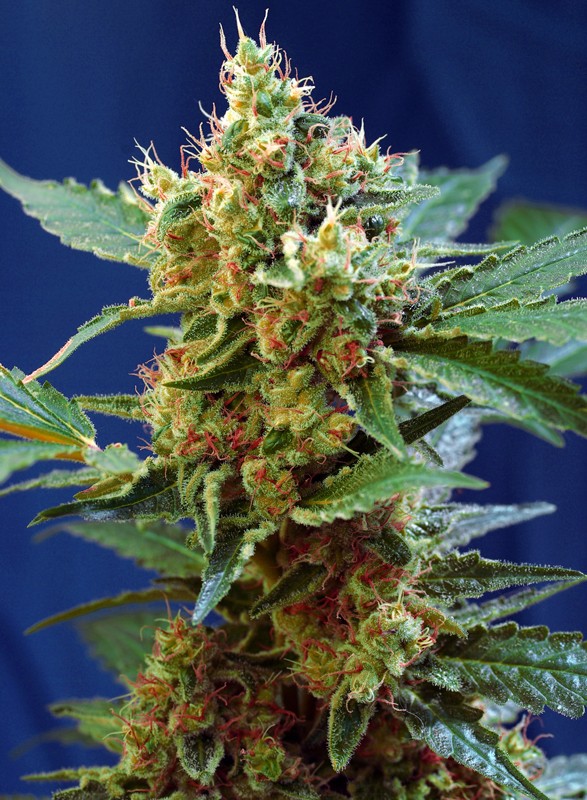

One of the first autoflowering strains released by Sweet Seeds®, Speed Devil Auto® (SWS11), was developed in early 2009 from a selection of specimens from a Canadian autoflower seed line, acquired through a seed exchange. Through multiple generations of selection, we believe this strain may be closely related to the famous and primitive Mighty Mite.